This history of the Brandstater family can be titled after a famous hero of Ancient Greece, Odysseus. He was a military leader who fought in the siege of Troy. And when that was done, he took ship for home with a band of brave warriors who trusted him. They wandered for years around the Mare Magnum, the Great Sea, enduring legendary adventures from hostile men and angry gods. The survivors at last reached their island home, Ithaca, and Odysseus was restored to his throne as King and to his queen.

The Brandstater story is like that. Our ancestors endured hardships and trials for centuries. They resisted persecution in their home country of Salzburg, and they lost their possessions and were expelled in the 1730s. They built a new life for themselves in East Prussia. But after many years these Germanic surroundings also changed in unhappy ways. There were many families named Brandstater among the Salzburgers and one of these, a family of six, decided they must make another new start somewhere else. Two young parents plus four children sailed out of Hamburg in 1871, and crossed vast oceans to the distant, primitive island of Tasmania. This was no civilized kingdom, ready to welcome them, and their future depended on the initiative, hard work and family commitment of a capable farmer-carpenter, husband and father named Emanuel.

Here, in this website, we are telling the story of how this Emanuel and his family, and the children’s children after them, built new careers and a new future for themselves and their descendants. Here is the story of the beginnings of the Brandstater family in Australia and its continuing expansion.

Expelled from Salzburg

The first Brandstater ancestors we know lived and farmed in the mountains and valleys around the cities of Salzburg and St. Johann. They were herdsmen and crop-growers. Many of them were refugees from elsewhere. In the 1600s and the early 1700s, the deplorable and appalling wars of religion that had long troubled Europe had led many persecuted peasant families to seek more hospitable places to live in, like Salzburg. They included numbers of devout Protestants, including some Brandstaters, who earned a living in the farmlands around the city. Some were Hugenots, religious refugees from France, and others had crossed the mountains from Italy, and who have been linked by historians to the Waldenses, victims of persecution from Savoy and Rome.

This peaceful-looking scene was disrupted in 1731-32 by Salzburg’s Archbishop Leopold Fermian. He admired the French king’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. This removed the royal protection that had sheltered French Protestant Huguenots, and many of them were thereafter compelled to leave France. In Salzburg the Archbishop decided he also should rid his territory of these Protestants whom he labeled troublesome heretics. So by edicts announced in 1731 and 1732, all Protestants, often referred to as Lutherans, were required to leave all their possessions and migrate to some other country. There was no massacre. But the expelled community that included many families named Brandstater, were forced to tramp with their children up the northern road that took them into friendly Protestant territory. All told 30,000 Protestants left the Salzburg area, and of these 20,000 accepted an invitation from King Friedrich Wilhelm in Potsdam to emigrate as a group and settle in his East-Prussian territory, in and around the city of Gumbinnen.

East Prussia

What kind of country was the new homeland that welcomed our dispossessed ancestors? East Prussia of that era was no backward, neglected corner of Greater Prussia. Known in all of Europe by its German name Ost-Preussen, it had a prosperous capital port city in Konigsberg, whose ships had easy and direct access to the Baltic Sea by a canal. Konigsberg boasted a magnificent royal castle, and the Protestant cathedral matched the finest in Europe.

The citizenry of East Prussia were a mixture, brought together by the ebb and flow of battles fought by leaders of Sweden, Finland, Russia, and Germany. Even distant France had great influence, thanks to Peter the Great, who embraced French tastes in art, in sculpture, in dress, in domestic decor and in architecture.

In that mix of peoples, religion was an important identifier, with Protestant Christianity being most dominant. However by the late 19th century Protestant worship had already split into several different streams, each with its own particular emphasis. Germanic Christians were divided into groups of Calvinist persuasion, and there was another group that was committed to the Arminian emphasis on free will and individual responsibility. Deep personal spirituality was emphasized by Moravian Christians from Herrnhut, who had had great influence on the Wesley brothers, John and Charles, in their founding of the Methodist movement in the U.K. and the United States. There were many believers who had come from Anabaptist background, and these families were pacifists. They were not comfortable with the increasingly militaristic policies of the Prussian political leaders, who were willing to use brute force to achieve their ends. These Christians did not want to see their sons marching off to war.

Another feature of note in early East Prussia was education. The University in Konigsberg had a diverse and disciplined faculty whose reputation was buttressed for years by the long tenure of Immanuel Kant as professor of philosophy. His book “A Critique of Pure Reason” was a landmark work, still widely quoted today. Preparing competent students to attend these demanding fields of study were strict schools in sizable towns, teaching serious classics at respectable gymnasium level.

The territory of East Prussia was an exceptional destination for our expelled Salzburger ancestors. Fifteen years before, that territory had been hit by a devastating epidemic of plague. In some of the farming areas the working population had been almost decimated, with many farms and even villages left empty, with insufficient workers to care for animals and produce its crops. To the Prussian King in Potsdam in the 1730s, the recently homeless Salzburgers were a godsend. These families responded gratefully, and moved right into the empty farmlands, especially around Gumbinnen.

The terrain itself was friendly for farming. The crop country around Puspern, when our forebears cultivated the fields there, must have been very similar to what Willi Beutenmuller and I saw when we first drove a rented car through communist territory in old East Prussia, now part of Poland, in 1989. I had been expecting to see a cold uninviting northern land, rather dull, with not much contented citizenry. But it was not like that. The farm country looked good: crops of oats and wheat, a full meter high in many places, and sure to yield a bounty of grain. I was especially impressed by the well maintained country highways, often running straight and smooth and flat for miles. They were the still-surviving autobahns of the booming German years of the thirties, often bordered on both sides by unending rows of mature beech trees. Many townships we passed through had suffered badly during World War 2, but those well-made roads and those splendid trees survived. In good times, this country could be very productive.

In the 1730s, the newly arriving Salzburgers had been assigned to vacant farms and villages, and they quickly did the necessary work of restoring the houses and land for active occupancy. The Salzburgers established a community with neighbors having a common history, a similar faith, and a shared determination to flourish in this new country. Sharing many features of religious faith, in the city of Gumbinnen they built a special church for themselves, to suit the specifications and worship practices of their fellow-believers. That humble original church became neglected and dilapidated when the German residents moved out and Russians moved in during the war years. When Willi and I were there initially it was in needof rehabilitation, but when I visited Gumbinnen again some years later, the church had been restored after permission had been given by the Russian government.It had undergone restoration and was looking good, with fine stained glass windows.

Why did the family leave?

Emanuel and his wife Carolina were not good letter-writers. They left us no clear account of the unpromising future for small farmers that made their family’s prospects in East Prussia look bleak. Later from Australia they may have sent reports to relatives back in East Prussia. But they kept no diaries for us to read, and no messages to help us connect with them. So we have to surmise from history for the reasons that led to their discontent and their urgent desire for emigrating to somewhere else.

In the 1870s economic pressures loomed large. There was a high economic and cultural value set on large families. But small landholdings were not large enough to support a large family and the farm would normally be handed down to the oldest son leaving other sons to fend for themselves. The First Family of Brandstater with Emanuel at its head, included three young boys, and Emanuel wanted to give all his children a good start in life. Also, the industrial revolution that supported the working class in Britain was late getting started in Prussia. Good jobs to support a family were too few in the cities, even in port cities like Konigsberg. There were not enough factories.

An alternative career for able-bodied young men was in the military. But enrollment in the army was undesirable, especially because of the brutal, life-threatening, hand-to-hand bayonet fighting that was the norm in Europe at that time. Furthermore, many Salzburgers had deep religious antipathy towards war and bloodshed. Anabaptists and Moravians had strong pacifist convictions. The Prussian army was well trained and disciplined, as demonstrated in 1871 by their victory in the Franco-Prussian War. But still there was tragic loss of many young Prussian soldiers. And Emanuel and Carolina may have had deep objections against seeing their sons march off to fight in other men’s dangerous wars.

In 1871 a further source of uncertainty for the Brandstaters was the rivalry, sometimes bitter, that had arisen between different communities of Christian devotees. Those serious believers held passionately to their convictions. And if you happened to express forceful theological views that were opposed to those of the rulers in your area, you could easily suffer for your beliefs. Sharp differences could lead to poor court judgments; time in prison was a possible penalty. The European Wars of Religion left behind hostilities that took decades to subside. We don’t know what convictions motivated Emanuel as a young man in East Prussia, but he did demonstrate devout involvement later in the religious life in their Tasmanian village of Bismarck.

Putting these factors together, Emanuel and Carolina became convinced that life for them and their children in East Prussia was not going to be as rosy as they had hoped. They heard reports coming from thousands of Europeans who had emigrated to Canada, the United States, Brazil or Argentina. And they wondered how they might be able to arrange their affairs, take leave of close family and friends, and undertake the exciting but risky and life-changing move to a wholly different culture. Hopefully it might lead to a new, fulfilling life for the whole family. A big obstacle for them would be the need for money to pay the costs of international travel. They would also need sufficient cash to survive for a time until they were settled in their new home and had found ways to earn income and support themselves.

Voyage to Tasmania

An answer to these financial quandaries came from an unexpected source: an official offer of assisted ship’s passage to a place about which they had known little. The offer came from a British Colony in far-away Tasmania, a large island south of the mainland of a continent named Terra Australis that is now called Australia. The government in the capital city, Hobart, under the rule of Queen Victoria and her governors, was in need of skilled workmen to do the rugged work of constructing roads and bridges and building houses and other structures in the towns and cities. Tasmania especially needed the skills of experienced farmers, who knew animal husbandry, could clear land of its forests, and establish farms for grain and vegetable production.

The announcement that came to the attention of Emanuel and Carolina described the terms of engagement. For an assisted passage it offered preference to experienced “German small farmers,” and that was a credential that Emanuel could satisfy easily. Our Brandstater ancestors must have discussed it thoroughly, and learned what they could about Tasmania, its climate, and its suitability for successful farming. We don’t know whether this offer was publicized by a newspaper, by notice posted in a public building, or even by announcement at church. But Emanuel decided this offer was very suitable for him and his family.

He was interviewed, probably in Konigsberg, a long trip from Benkheim, by a representative of the Tasmanian government. He was a German-speaking Tasmanian named Frederick Buck, who had been given the temporary title of Tasmanian consul. And all seemed favorable except for one detail: all family members had to have good physical health. Emanuel had to report that their daughter, Louisa aged eight, had a hearing disability, a fairly advanced level of deafness. By standards set in Hobart, that made her unacceptable as a recipient of an assisted ship’s passage.

What to do? After agonizing debate, a solution was found. The two parents, Emanuel and Carolina, plus the four remaining children (Emanuel Jr, Gustav Adolph, Carolina Jr, and a new baby, Herman) would accept the assisted passage, all the way from Hamburg to Hobart. And young Louisa could stay behind in the care of two aunts, sisters of Emanuel, who knew the child well and could be trusted to take good care of her. The sisters lived together in a small village called Seehausen, located within the large Puspern property and next to a small lake. A nearby village called Ipatlauken included a school which was suitable for Louisa. And her parents were confident that, once settled in Tasmania, they could earn some money and pay the travel expenses to bring Louisa out to join the rest of her family.

That custody arrangement with the sisters was not ideal, but it was seen as only temporary, and Emanuel set about all the other arrangements that had to be completed before the next passenger ship that would sail to Hobart. Family and friends, especially those in Benkheim where Carolina’s Lange family were living, had to be drawn into this major family separation. Some possessions were sold, yielding travel cash, and other household stuff was left with the Langes. When the departure date was near, we can assume they had a farewell party of sorts. Shedding many tears, the family members did not know if they would ever see each other again. So Emanuel and his family started their journey to the Port of Hamburg. We don’t know whether they traveled by highway coach, or whether by this date in 1871 the European network of railroads had reached Konigsberg.

Another travel option might have been a coastal ferry by sea from Konigsberg to Danzig or Lubeck, and the rest of the way by overland travel. They had to reach their port of embarkation in time to board ship before the set departure date. Their ship, the SS Eugenie, was a pure sailing ship, so they were dependent on changeable weather and wind conditions to give them good sailing down the Elbe River to the Atlantic. In case of delays, passengers would have to spend some of their savings in the riverside lodging houses, built expressly to accommodate the large numbers of departing emigrants (called “auswanderers” in German) that said farewell to Europe every day. The wharves were often crowded. During decades, Hamburg was the principal port of departure for millions of exiting Europeans.

Caring for departing passengers became a major industry at the Port of Hamburg. Precise records of every single departing passenger were kept in an Embarkation Book, and all the books for year after year were protected and closely guarded, kept safe in a historic Embarkation Museum in Hamburg. Willi Beutenmuller and I were able to visit this museum during our visit to Hamburg in 1989. And we inspected the exact 1871 book in which were listed the names of all six members of the Brandstater family, including the babe-in-arms Herman, who sailed from Hamburg on the ship SS Eugenie. We gazed for a long time at that historic page. In German longhand writing it was easy to read the names of all six members of the family, their surname being spelled in the original way, Brandstaedter. All their ages were given, and also Emanuel’s occupation, which was recorded as “farmer and carpenter”.

It was in that Embarkation Book that we learned, for the first time, where, in all of East Prussia, our ancestor family had been living at the time of their departure. This was their place of origin, the town of Benkheim in the heart of East Prussia. That was an important place in family history, and both Willi and I independently came to the same conviction. If it’s at all possible, we must visit what remains of Benkheim, to see where the Brandstaters had lived, and inspect the local church where they might have worshiped. We might even discover some remnants of the family history.

Now we must tell what kind of ship the family sailed on, and about the conditions on board. The Eugenie, built in Hamburg shipyards in 1865, was a steel-hulled vessel, rigged as a brigantine, with tall masts and big square sails. Without supporting steam engine power, the sailing times were determined by prevailing winds. The crew were European, and the skipper was Captain Voss. The embarking passengers numbered about 250, though about a hundred of them disembarked at an unnamed destination in Brazil, leaving a lighter crowd, about 170, to share facilities for the rest of their voyage to Hobart.

On board the conditions were elementary and primitive. There was little privacy between families, just many narrow bunks crowded together. Bathroom facilities were pathetic. There was water for bathing, but bathroom relief was usually achieved by visiting a bench that hung over the stern of the ship. This was no pleasure cruise. Little space was provided for just sitting and socializing. And the food offered by the cook at mealtimes was basic meat-and-potatoes stuff, with little fresh vegetables. There were not enough dining tables for all passengers. So much of the mixing and eating and fraternizing took place in the below-deck sleeping spaces, sitting on adjacent beds. These crowded, uncomfortable conditions led to sickness amongst the passengers, and the lack of fresh vegetables and fruit resulted in several cases of scurvy during the five-months at sea. During the voyage there were four deaths amongst passengers; the cause for any of them was not recorded. And there was one, normal, vigorous childbirth in mid-ocean.

The ship’s ports of call were an unnamed port on the Brazilian coast, followed by a bearing southeast across the south Atlantic, with an assumed call at Capetown for fresh water and food supplies. After rounding the Cape of Good Hope, all Australia-bound ships sailed due east at a latitude in the famous Roaring Forties. That was about 45 degrees south, where the trade winds blew unceasingly, often at close to gale force. The ocean waves were mountainous, towering over the ship when it was deep in a trough between crests. It was exciting and rough sailing, but with those strong westerly winds daily distances gained were large, every day taking them nearer to Hobart.

Hobart at last

At last the Port of Hobart came into view. The date was in 1872. What a welcoming sight, with a large, quiet, sheltered bay, and behind it lofty Mount Wellington serving as a backdrop! We can only imagine what were the thoughts of Emanuel and Carolina as they saw at last the terrain that was to be a future home for them and their children. It was so different from the flat, farming country they had known in East Prussia. But this was their future home, and it was here that their new lives would unfold.

The arrival of the immigrant ship the SS Eugenie was a significant event in Hobart, reported prominently in the city’s newspaper. But surprisingly there was no rush for the passengers to disembark. The identity of all arriving newcomers had first to be verified, and likewise their state of health. The Brandstaters were interviewed and their names duly listed in the port Landing Book, their names recorded in the Anglicized version, Brandstater, which we have used ever since. At last they were recognized as approved residents of the British Crown Colony of Tasmania.

But newspaper stories reported that the passengers remained together on board the ship for two more weeks, refusing to leave the ship until port authorities agreed to conduct a hearing at which they could voice their complaints about conditions on ship. During the voyage the food supplied was unsatisfactory for long months at sea. In one report we have seen reference to complaints about the behavior of Frederick Buck, the man who had recruited them, and who accompanied them on the voyage. This was a part of our ancestors’ adventure, and we had hoped to share here some details from a printed report of that hearing. But our searching, even with help from port authorities, failed to uncover any official report. What did emerge was a well composed letter written by passengers and signed by many of them, expressing sincere thankfulness to Frederick Buck for his help and his care for them during the voyage.

Employment at Cambria in Swansea

At last the passengers did come ashore, and were housed briefly in a harbor-side building. Some of them were welcomed and offered housing and work by relatives and friends from the Old Country. But the Brandstaters, and many others, remained at the port, available for employment. A newspaper announcement was published that gave a list of all the named immigrants, including Emanuel Brandstater, who were seeking jobs and housing. But his name was missing from a second notice posted soon after, indicating that he had obtained employment. In the official record, easily read today in the port’s Landing Book, there was a notice that told that immigrant Emanuel Brandstater had been employed by John Meredith, the proprietor-owner of a large farming estate at the town of Swansea on the east coast of Tasmania. His terms were to work as a farm hand, with undefined duties. He and his family would be given housing and food on the property, plus twenty guineas a year. That meant twenty golden sovereigns, each carrying the Queen’s profile.

In 1872 Tasmanian Swansea was a town in the making. Its name is familiar to anyone from Wales, where today stands a large city with the same name on the Welsh south coast. The range of mountains, which is the north-south topographical backbone of Wales, is called the Cambrian Mountains, and the Meredith farming estate was given the name Cambria, which it still has. The early Meredith family likely had robust Welsh connections. Their estate was a grazing property of about 15,000 acres, populated by thousands of sheep. Caring for this huge flock, protecting them from parasites by drenching, and helping with the big job at shearing time, provided plenty of work for a resourceful man like Emanuel. Even as early as 1872, fine wool from healthy sheep in the colonies was a valued commodity for the weavers of worsted cloth in Yorkshire’s Leeds and Huddersfield.

The two Brandstater sons, Emanuel Jr (10 years) and Gustav Adolph (six years) were too young for heavy work, but were at the right age, by English schooling tradition, to attend the Swansea public school. It was located an easy walk from the family’s housing at the farm. The boys were kept busy, learning new English words every day, confirming the German alphabet they had learned in East Prussia, and catching on to the rough and tumble of Australian kids in the playground.

The move to Sorrell Creek (later Bismarck)

Though Emanuel’s original contract was for two years of employment at Merideth’s sheep grazing estate Cambria, in Swansea, they may have stayed longer than that. They eventually made arrangements to settle closer to Hobart in a recently opened settlement called Sorrell Creek. This was about twelve miles from Hobart, inland from Glenorchy, a northern suburb of Hobart. The settlement was reached by a mountain road that led up and over a long steep hill, and was named Sorrell after an early Tasmanian governor. The family must have travelled from Swansea the same way as they came, by coastal ship, because there was not yet a navigable overland highway to Hobart.

Emanuel and Carolina were attracted to Sorrell Creek because that valley was suitable for timber milling and for farming in a well-watered valley. Sorrell Creek was an important destination for them because a a rather large number of European immigrants had already settled there. These included some German families they knew well from their shared voyage on the ship Eugenie, and from an earlier immigrant vessel the Victoria that had also brought German settlers and some Danish immigrants from northern Europe. The Brandstater family promptly settled on a 37 acre parcel of land that Emanuel had acquired from government authorities. Word-of-mouth anecdotes tell that while they were building a house on the property the family sheltered in some kind of temporary tent erected against a large hollow tree log.

When Emanuel had secured some employment for himself, and he had started the beginnings of a mixed farm, he built a complete homestead for his growing family. And that homestead remained the Brandstater House, and it still stands today. It was last occupied, as far as we have learned, by the Fehlberg family. A younger member, Don Fehlberg, has related to me that he had lived there with other family members in the 1920s or 1930s. In late 2017 I paid my respects to history by visiting the Brandstater House, now deserted and slowly decaying, with some kitchen windows broken. But inside it was dry, and had some surviving wallpaper. The corrugated iron roof seems to be intact, and the timber frame of the house seems to be strong and straight. I even crawled underneath and confirmed that the supporting stonework had held up well, despite the passing of 140 years. The whole property could be restored and made habitable, by anyone who felt inclined to invest in it some money and lots of love.

The one feature of this Brandstater country house that I missed on this last visit was the outback toilet, referred to as a dunny, which is a widely reverenced symbol of life in the Australian bush. On a previous visit in 1989 I had admired this traditional outback toilet. It was not painted, and was constructed of split gumtree wood, greyed from many years of exposure to the elements. To complete the picture, it was inhabited by the traditional redback spiders. But in the intervening years that historic edifice had been taken down, and nothing of it now remains.

Getting established in Sorrell Creek-Bismarck

It is necessary now to include here a summary of the fortunes of that First Family. Emanuel Sr, the patriarchal immigrant who was, with his family, the initial Brandstater pioneer in Australia. He made good use of his German training in carpentry and construction. In 1876 he was awarded a contract to construct a public school building and an adjacent schoolhouse on the main road leading into the village of Sorrell Creek. By that year the large number of German settlers in the valley wanted to give special honor to their Fatherland hero, Otto von Bismarck. So they officially named their farming township Bismarck. The town name of Bismarck remained until World War One made German names became unpopular in English Australia, and after receiving a community petition, authorities in Hobart changed the name to Collinsvale. The original school that great-grandfather Emanuel had built in 1876 was much later badly damaged by a bushfire. But it was rebuilt in enlarged shape, long after the series of young Brandstater kids had received their basic education within the original walls.

In order to understand what life was like in Bismarck in the early years, we urge that you to read the memoirs of my father Roy Brandstater who was born in northern Tasmania (Melrose) in 1898, but spent most of his childhood in Bismarck where he received his elementary education. He speaks of Collinsvale, as do many others, as a hard-working community of good neighbors. In his Memoir Roy gives special description of the annual community picnic which was a gala affair, with plenty of sporty competition, stacks of food, and music to suit any taste. For some years, Bismarck fielded a local brass band in which both Gordon and Roy played instruments. The annual picnic was always held, according to his record, on Stellmacher’s farm.

The economy of Bismarck depended on two main industries: timber milling and farming. Timber milling was a natural industry because there was an abundance of large-trunked eucalypt trees, of which several varieties flourished in the climate of Bismarck. Furthermore, that forest of sturdy trees had to be cut and the stumps removed before the land could be used for growing edible crops. All the Bismarck men became excellent woodsmen, expert with saw and axe. My father Roy, as late as his mid-seventies, could still demonstrate remarkable skill with an axe. He could look at a log, judge how to attack it, and cut it through quickly with a clean scarf, like any champion woodsman.

Farming was the other important industry. In Collinsvale it mostly consisted of small mixed farms, with an emphasis on growing fruit crops: apples, gooseberries and raspberries, along with vegetables. Much of the land was sloping down into a narrow valley, and those mixed farms could prosper only with lots of hard, hands-on work.

What about church and religious life?

One feature of life in Bismarck was the emphasis on disciplined, devout behavior, appropriate for upright European citizens. Almost all of the settlers were Protestants, identifying with a connection to some version of the Lutheran church, or similar denomination. But there was no local pastor to lead them in weekly church services or worship. There was only a small chapel that was sometimes used for Methodist worship.

In 1880s a change occurred in the religious life of the community. The village leaders chose to invite some international Christian preachers to take a break from Hobart and visit Bismarck. There were several persons in this visiting party, including men named Haskell and Israels. These men were robust, conservative, Bible-quoting preachers from California, and identified themselves as Seventh-day Adventists. They preached emphatically and with persuasive sincerity. They preached with particular emphasis on the Fourth Commandment that required observing Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, as the day for rest and for worship. The village audience was convinced that the Bible did indeed urge the sacredness of the Sabbath, and almost all decided: If that’s what the Bible says, let’s do it.

The small Methodist chapel was not offered to these new converts for worship. The men in the village, including Emanuel Brandstater and his family, quickly decided they should build a church for their own use. One of the settlers, August Darko and his wife Henriette, offered to donate a fine block of land on a central location on the corner of Church Street and the Main Road. That offer was gratefully accepted by the community, and a willing team of men set to work. With expert guidance from Emanuel Brandstater, who had demonstrated his competence by building the public school, a fine church building took shape. Emanuel was helped by willing volunteers who included his sons Emanuel Jr, Gustav Adolph, and Charles Albert. The simple but triumphant church building was finally dedicated and used for worship in August, 1889. Virtually all of the growing Brandstater family residing in Bismarck worshipped in that church week by week. Father Roy told me that his earliest childhood memories were of himself, as a toddler, sitting on a front pew and dangling his little legs, while learning the simple hymns of the day. Music, much of it sacred, became a major element in the cultural life of Bismarck.

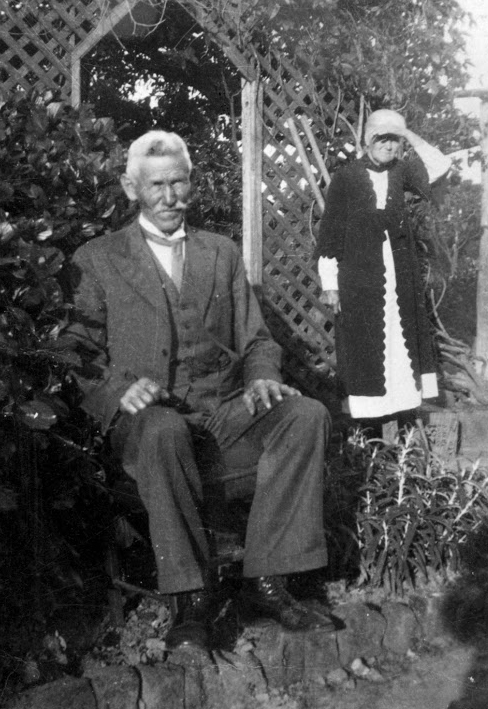

Emanuel continued to care for his mixed farm the rest of his life, eventually retiring with his wife Carolina and spinster daughter Carolina to a colonial house on the Main Road in Glenorchy. While living there, Emanuel died in 1911, aged 78.

R.I.P Emanuel Brandstater

Emanuel’s children lived after him and here we can summarize their names and their life course:

- Emanuel Jr, oldest son, at age 22 married Wilhemine Darko, age 25, and produced eight children, of whom seven reached adulthood. They were: Ernest, Annie, Louisa, Lydia, Ida, Gordon, Roy. Ernest led the way. Annie was a favorite, but unfortunately died in a traffic accident in Glenorchy, before her planned wedding. Louisa worked with Uncle Gustav Adolph, married William Smith and served many years as pioneer missionaries in Pacific Islands. They had two sons Ivan and Milton. Lydia remained in Tasmania, married farmer Fred Peterson, and had no children. Ida was the youngest daughter and found domestic employment in Glen Huon, married Herb Brown, had three children Ron, Stan, Yvonne. Gordon as a teenager, sought more education at Avondale College, became an Adventist minister, married Idarene Felsch. He had three children: Russell, Marjorie, Beryl (Betty) and was church leader in Pacific islands and in Australia for many years. Roy followed Gordon to Avondale, became an Adventist minister, evangelist and church builder. He married Frances Eastwood, had four children: Rhona, Bernard, Murray, Lynette.

- Louisa: was second child, had hearing disability, remained with relatives in East Prussia. She had two daughters, Louisa Jr. and a second name not known.

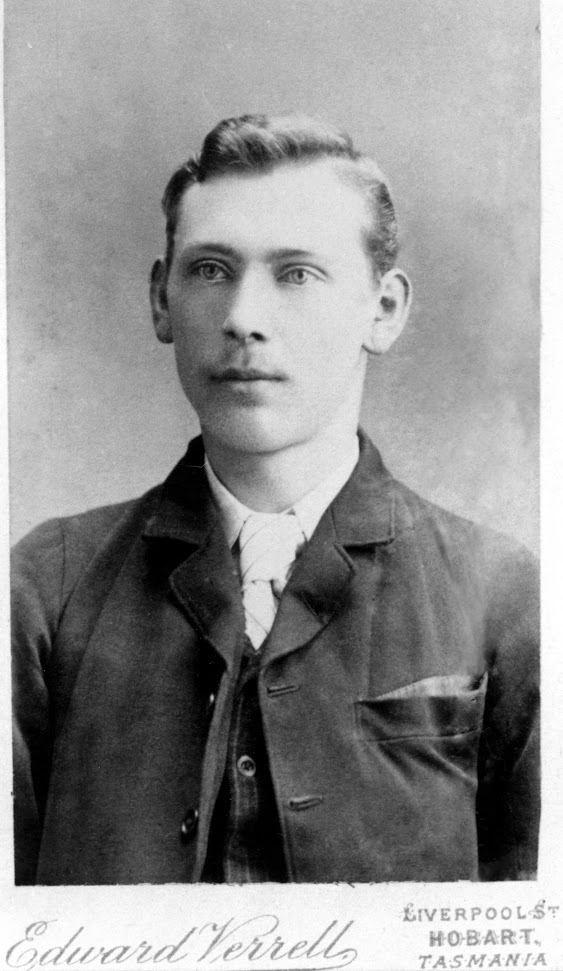

- Gustav Adolph: following advice from Ellen White, he studied at Battle Creek College, graduated in nursing and subsequently managed the Adventist Sanitarium in Christchurch. He later worked in Sydney and Warburton. Married Florence Grattidge and they had four children: Grace, Myrtle, William and Reuben.

- Carolina: daughter, never married.

- Herman: became a farmer in Bismarck, later a house builder in NSW. Married Minnie Hughes: two sons Reg and Cecil. Fondly remembered.

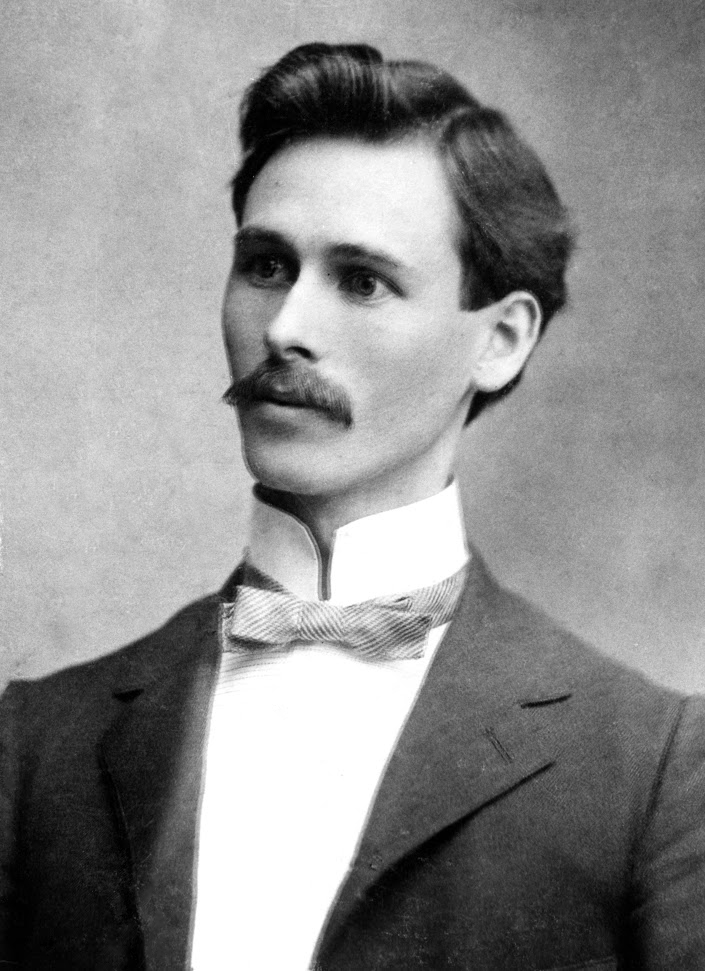

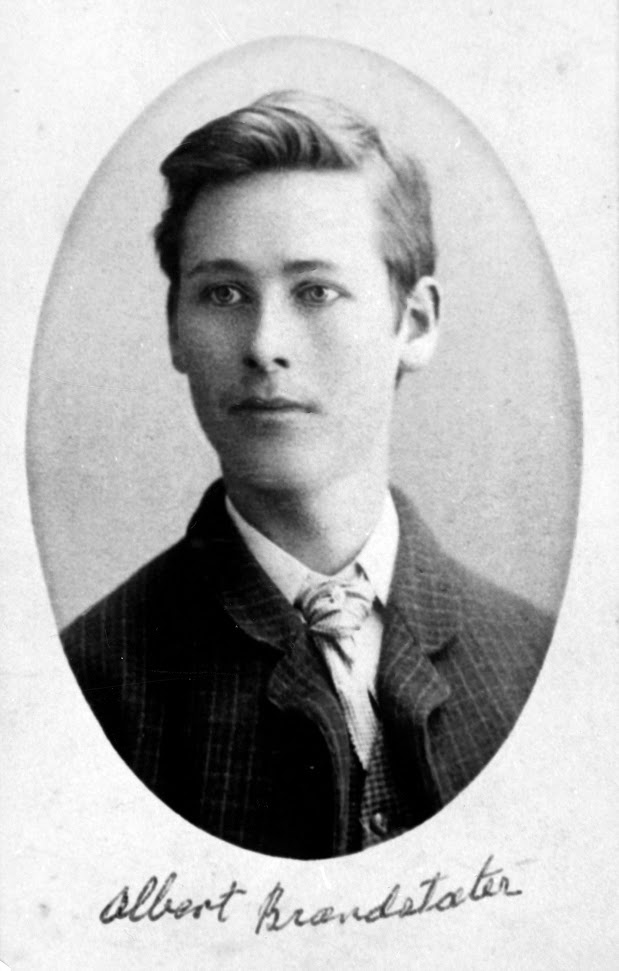

- Charles Albert: known as Albert in Australia, as Charles in California. Studied in Battle Creek. Married Margaret Kessler. Lived most of his life in Los Angeles and worked as a practicing dentist. He had three sons: Oliver, Glenn, Kenneth, all dentists.

- Fritz: A loner farmer and musician. He lived life in Tasmania and never married.

- Charlie: Became credentialed house builder and contractor; worked in Tasmania and Geelong, later NSW. Married a Smith daughter. Had two daughters: Beryl and Thelma.