This is an account of the life of Emanuel Brandstater Jr, oldest child in the first family of Brandstater immigrants who arrived in Tasmania in 1872. This Emanuel was an important figure in the unfolding of the Brandstater family in Australia. He was big in body and big in heart. He lived an active life that touched many other lives, and he produced seven children who made notable impacts on their own offspring and on the world about them. So to do justice to his memory will require that we tell to his story in some detail.

This Emanuel Jr was the first child of our Emanuel Sr and his wife Wilhelmina Justies, both being natives of the city of Gumbinnen in East Prussia. Their Baby Emanuel was born in 1862, and his birthplace, recorded in his naturalization papers, was a place called Surmunin. We have not located this place exactly in early maps, but it was probably a small town close to Konigsberg, the large capital city of East Prussia. At that time his young parents would have been living close to Emanuel Sr’s place of employment, as carpenter and shipwright in the busy Baltic seaport nearby.

There are few records about Emanuel’s early life. He was ten years old when his family made their epic migration and voyage from Hamburg to Hobart. He had spent those prior years in a German culture, with German-style schooling, learning German alphabet and reading, plus doing some basic arithmetic. He left no letters, no written schoolwork, and no comments about his early life in East Prussia. He had to start a new education when he arrived in Tasmania as a ten-year-old. He attended a public school in the seaside town of Swansea, where his father had found his first employment. And we can assume that his Germanic tradition of disciplined attention to study helped him to get an early grip of the English language that surrounded him there.

With no typewriter, and limited skills in written English, Emanuel left behind no handwriting except his personal signature in a book rescued from the library of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in their final living-place, Bismarck. This was a farming village about twelve miles from Hobart, and the new-coming Brandstater family settled in that village as their eventual long-term place of work and residence. While he was no literary scholar, Emanuel certainly could read. And at a time when books were an expensive luxury in a humble farmhouse, he had access to a lending library in the family’s church.

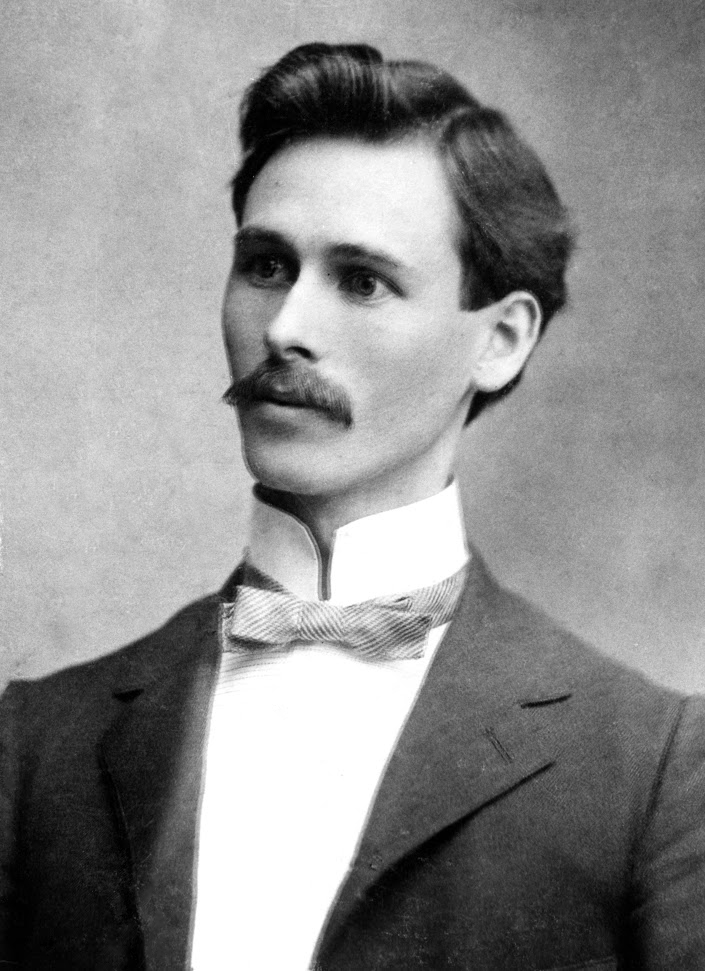

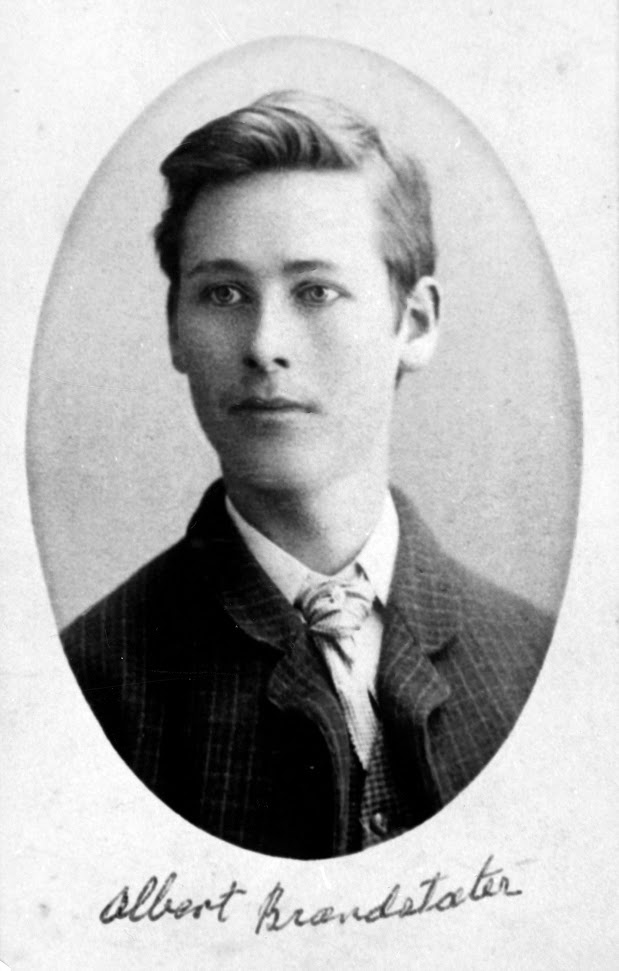

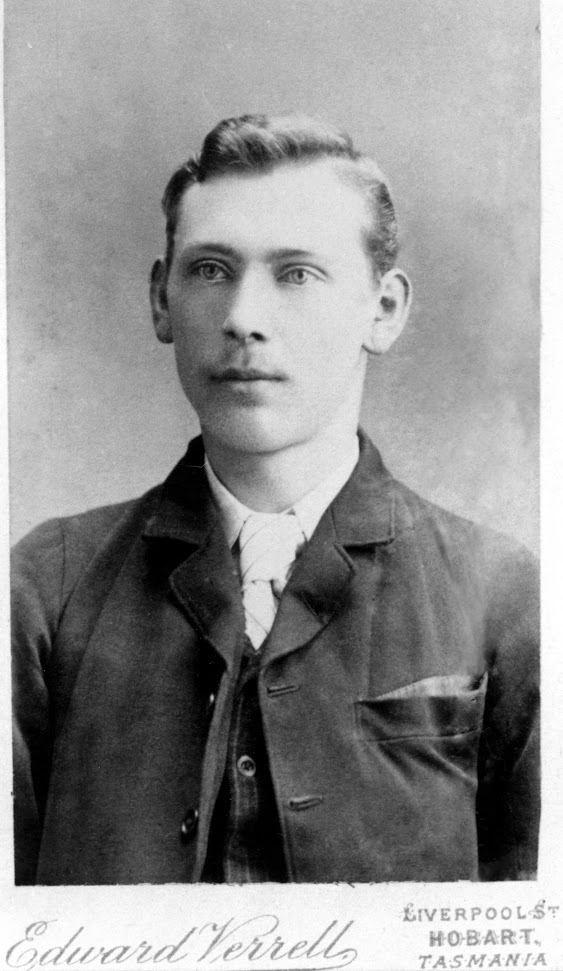

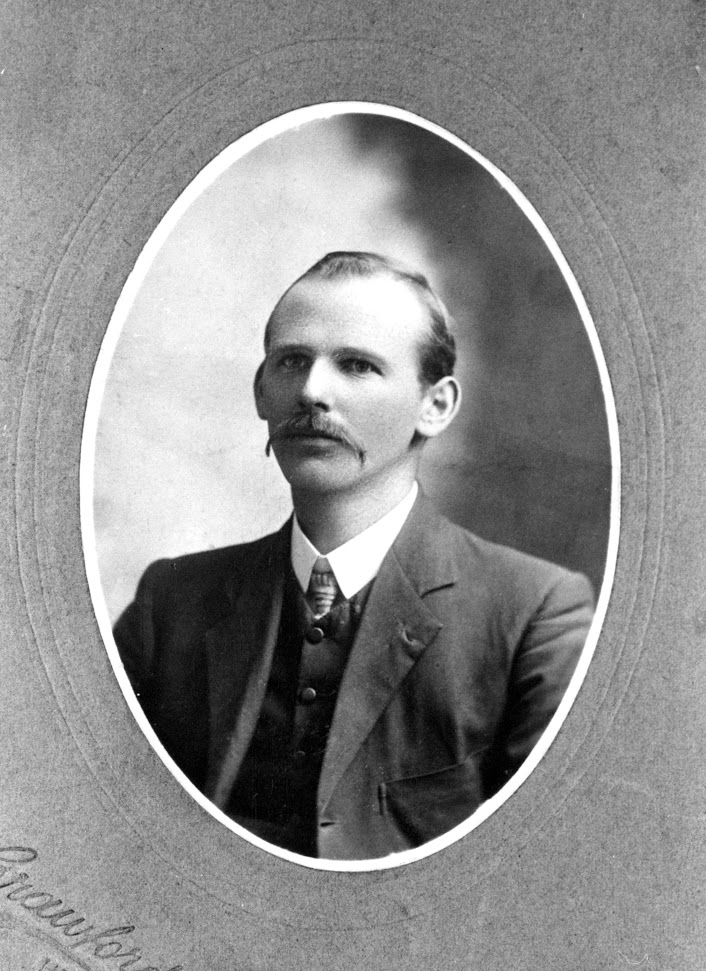

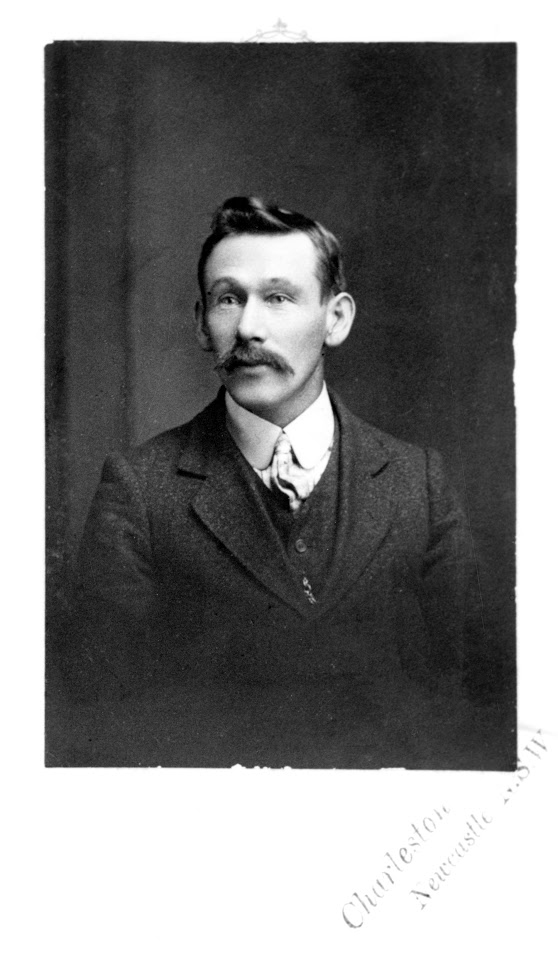

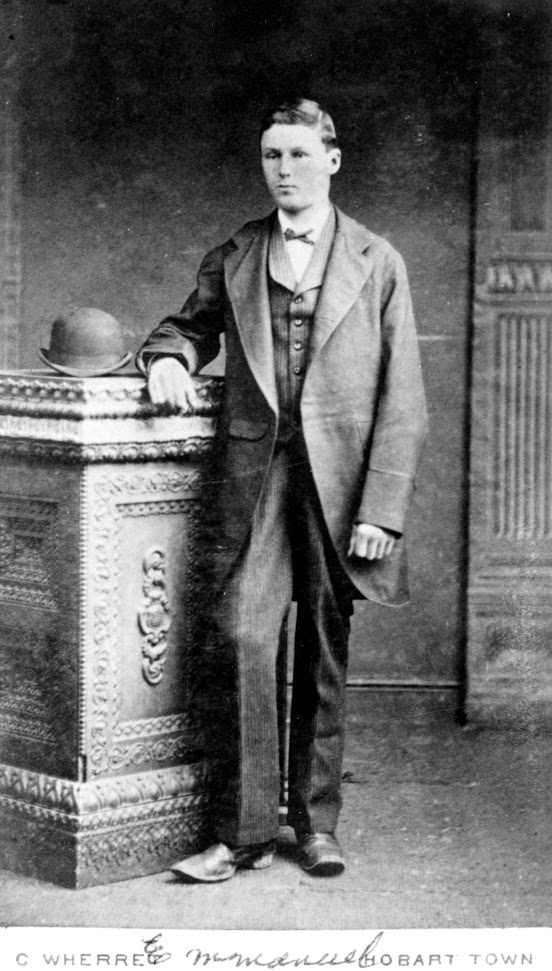

Our first photograph of Emanuel Jr shows him as a teenage boy, with no indications yet of the robust physique that lay ahead for him. Yet he is dressed in a full suit too big for him, and even sporting a bowler hat, scarcely suiting his age. In this photo he is shown in the early years when the family was settling in Bismarck. Yet it is noteworthy that even at that early stage the family attached importance to making a portrait record, a landmark photograph of their eldest son. And similar portrait photos were also recorded, later, of the other Brandstater young men, Gustav Adolph, Herman and Albert, when they arrived at the critical age of approaching manhood.

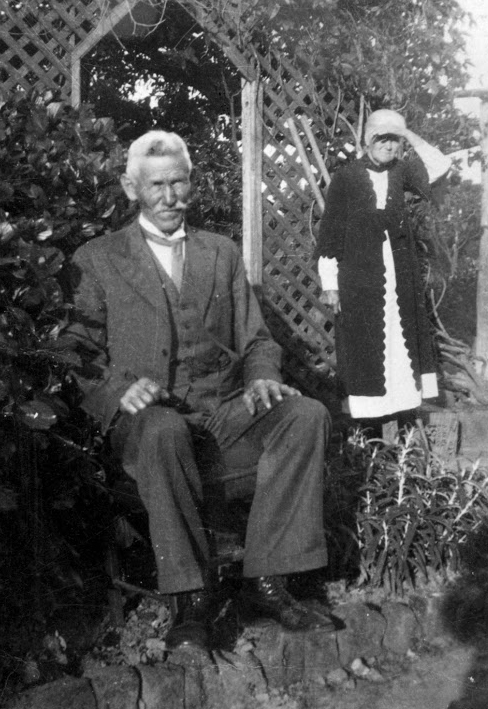

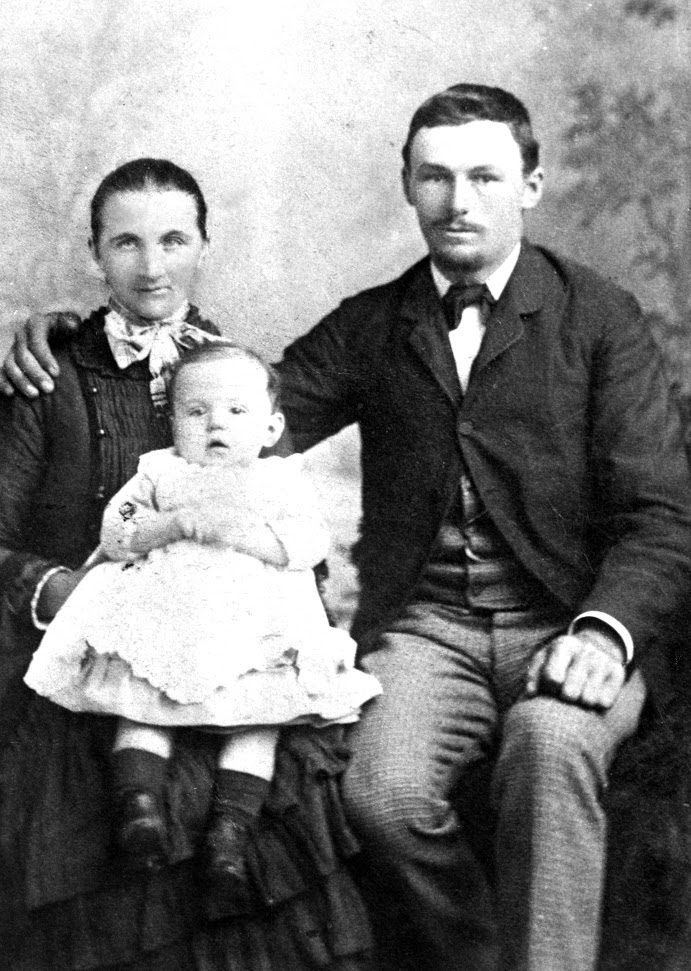

After that early photo of Emanuel, we have no other image of him until he shows up, about the year 1900, as a strong figure in a much later historic portrait of the original Brandstater family. He is shown sitting beside his father, with his wife Wilhemina standing beside him. The photo is a unique record that shows Emanuel Jr as a robust man of about 38 years of age. It also shows the other family members also in a good year. About 28 years had passed since their arrival in the “Eugenie.” But the family photo came many years later, when all scattered members of the First Family had gathered back home for a rare reunion. They posed for the camera in front of the original homestead built by Emanuel Sr on Springdale Road in Bismarck. The senior pioneer family heroes, Emanuel Sr and wife Carolina, were seated in the middle up front. Albert had returned at last from his studies in Battle Creek, with his wife Margaret. Gustav Adolph was home from his work in Christchurch. Herman was there too, with his wife Minnie. To complete the family, Carolina Jr (“Lina”) was there also, a spinster. That ancient house still stands there today (in 2018), abandoned and deserted, engulfed by trees and shrubs, sad and slowly decaying.

We need to return to young Emanuel Jr in Swansea. At that time in Tasmania, immigrants who had been transported to Tasmania under an assisted passage scheme were required to complete employment for a period of two years with an established settled citizen, to help repay the cost of their ship’s passage. So Emanuel Jr had spent about two years in the Swansea public school by the time the family had learned the new culture, felt stabilized in their new land, had perhaps saved a little money, and were ready to move on. That first stay in Swansea had been a good beginning, but they now moved to their permanent home in a place called Sorrell Creek, named after an early governor of Tasmania. This was a settlement in a secluded valley, about twelve miles from Hobart, a few miles off the main road north, and close to Glenorchy, a northern suburb of Hobart.

With an influx of new European settlers from two ships, the “Victoria” in 1870 and the “Eugenie” in 1872, Sorrell Creek soon found itself populated by a strong German-Danish mix of recent immigrants. In their hearts many of them were still celebrating the 1871 Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian War, and were proud of the unification of the German states to form the German Empire. These events had taken place under the leadership of their national hero, Otto von Bismarck. So they gave his name to their farming village, calling it Bismarck. It was here that Emanuel finished his schooling in English, in the new classrooms constructed by his father in 1876 under government contract. He probably left school at the age of fourteen, and could then shoulder his responsibilities as the eldest son, helping his dad with the rugged hands-on work on the farm, in logging, or in construction jobs.

Advancing through his teens and at last into vigorous young manhood, Emanuel began searching for a wife. There was a limited number of eligible young women in their rather small farming community. During times of active immigration, arriving ships usually brought more risk-taking young men than women. But Emanuel did find and marry Wilhemina (“Mina” or “Minnie”), a daughter of August and Henrietta Darko (original German name “Darkow”). In the Tasmanian General Register Office their marriage took place on 8 January 1885. Emanuel’s occupation is listed as “carpenter”. His age was 22, and Minnie was 25.

This young couple needed to shape a career for themselves, and establish a home for the family that they hoped for. Emanuel’s employment options were limited. In young manhood Emanuel had joined with his devout Christian parents in their beliefs and practices of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. For a time, he worked in the role of “colporteur,” which is a seldom-heard word today. It required the door-to-door selling of books, and those that Emanuel was selling were on religious and health subjects, published by Seventh-day Adventist publishing houses. This work took him to another fruit-growing country district called Glen Huon. It was a rich, productive valley some fifty miles on the other, south side of Hobart. As a result of his selling a substantial number of books, a lively religious interest was created amongst the citizens of Glen Huon. Because of his inexperience with such matters, Emanuel called for help from a Bible teacher in Hobart. Soon an active worshiping company took shape in the district. In this way Emanuel was instrumental in helping to establish the Glen Huon S.D.A. church.

From his work selling books, and discussing them with thoughtful customers, Emanuel must have become more aware of other potential career possibilities beyond the boundaries of his farm surroundings. But he had obligations because of his status in the family as firstborn son, and the immediate needs of his wife and young children. He was four years older than his next younger brother, Gustav Adolph, and next came Herman and Albert, with fewer obligations. They were free to envision a larger world out there, with broader horizons than their quiet country village could offer.

So it was that two of those brothers, first Gustav Adolph, and later young Albert, left Bismarck in the 1890’s to seek further education in health care, and traveled to Battle Creek College in Michigan, where they studied under the disciplining eye of notorious Dr. John Harvey Kellogg. This thrust into higher education was a new, and perhaps surprising, direction within the Brandstater family, who in East Prussia had been farmers and laborers. They had had little expectation or opportunity for higher education. So Emanuel, the eldest son, applied himself to immediate tasks close at home, while Gustav and Albert were studying in Battle Creek.

Nevertheless, Emanuel was a man of energy and purpose. In the early years he had learned many practical skills from his father, and from one of his workplaces he had been able to learn the basic construction and mechanisms of steam-driven machinery. He could operate them, and when necessary, fix them. This was not formal education or apprenticeship. He simply had a natural aptitude for grasping the workings of things mechanical. He became the Bismarck expert for sharpening a blunt cross-cut saw, or for fixing somebody’s house clock that had stopped working. Through his skills at carpentry he became the coffin-maker for the community. As described by his son Roy, Emanuel was the leading man in the village to whom everybody would go when they had a mechanical problem to solve.

For several years, before the end of the 19th century, Emanuel’s growing family lived with him in Northern Tasmania, where he had a government job in road and bridge-building projects. After starting with baby son Ernest in 1886, an additional child was added to the family every year or two. It was here that the younger sons, Gordon (in 1896 in Upper Castra) and Roy (in 1898 in Melrose) were born. Their births were registered in the nearby town of Ulverstone, west of Davenport. Roy was one of eight children born to Emanuel and Minnie. One baby, Florence, died in early infancy, leaving seven vigorous survivors, of whom Roy was the youngest. Details of these children and their later careers are described elsewhere in this family website.

From Northern Tasmania Emanuel moved his family back to their original home territory in Bismarck. At an early stage they occupied a small house on Springdale Road, located, Roy once told me, behind August Totenhofer’s farm. These neighbors were also from East Prussia. It was from that time that Roy could later recall his earliest childhood memories of being led, as a mere toddler, across the rough fields between the house on their farm and his grandfather’s house a half-mile away. Roy remembered that from those earliest years, his closest playmate and pal was Howard Totenhofer, who later became a distinguished artist and a lifelong friend.

Emanuel moved his family again, this time to what was called “the church house”, situated behind the S.D.A. church, and owned by Minnie’s parents, the Darkos. The whole family now included: Ernest (born 1886), Annie (1888), Louise (1890), Lydia (1891), Florence (1892: died aged 2 months, cause not known), Ida (1895), Gordon (1896), and Roy (1898).

About this time Emanuel joined in a business partnership with his younger brother, Albert, recently returned with his American wife Margaret Kessler from studies in Battle Creek, Michigan. The two brothers established a sawmill in the heart of Bismarck on the banks of Sorrell Creek, near to where the Main Road now crosses the Creek by its bridge. Just beyond that bridge, a street on the right was opened by the county to give access to the mill, and this street today is signposted with the name “Mill Road”. That Brandstater mill was a successful enterprise, responding to the great demand for sawed construction timber. To provide Albert’s American wife with some of the amenities she was accustomed to back home, Emanuel assigned to her and Albert the occupancy of a fine new house he had originally constructed for his own family.

For his personal needs Emanuel took his own large family to live in a newly built house some distance away at the end of Valley Road. This place, with its surrounding farm, remained the family’s home until several older offspring moved out of town. It later became the farm property of Fred Peterson, who tied himself to the family by marrying Emanuel’s daughter Lydia. In 1939-40, I (Bernard) spent several weeks as a guest in that very same Peterson house, just a ten-year-old lad on a year-end vacation from school. I slept there, worked there, and ate meals with Fred and Lydia. Fred is memorable for me because of his practice of cleaning food from his false teeth at the end of a meal. In a different domain, Fred was a musician. He played a competent baritone instrument in the Bismarck brass band. At Fred’s farm I learned how to use a churn and turn thick cream into butter. I helped with fruit picking and other farm jobs that were new to a city-bred lad. Traveling from Sydney to Tasmania with my Uncle Herman, I think my parents sent me on this holiday to reinforce my connections with the family history in Bismarck, now renamed Collinsvale, while back in Wollongong, they were preparing for the arrival of their youngest child, Lynette.

Emanuel’s successful mill in Bismarck had a bright but short life. It was totally destroyed in a disastrous fire of unknown cause. With the mill gone, the brothers’ mill partnership collapsed, and Albert chose to take his wife back to California, where he changed careers and entered dental school. In 1978 I accompanied my father, Roy, back to the site of that Bismarck mill, which had been Emanuel’s proudest achievement. The mill site and the memory of the fire disaster were familiar to Roy. From Mill Road he and I crawled through a fence and down a grassy field to the shore of Sorrell Creek. We saw no trace of the mill structure itself. The mill and its machinery were gone. But Roy was persistent and kicked over some areas on which he was standing. And there, in more than one place, his foot unearthed some unmistakable sawdust. On the surface it looked black, like ordinary dirt. But when he kicked over the surface and exposed the ancient sawdust underneath, it looked fresh and light-colored, just as if it had come yesterday from the mill’s circular saws. In fact, it had remained there for 70 years, sealed off from normal atmospheric oxygen that would have been discolored it.

Tragedy of a different kind overtook the family later, when Annie, Emanuel’s eldest daughter, returned to Bismarck after a stay in Christchurch where she had been working with her Uncle Gustav Adolph. He was busy in that New Zealand city, developing a new treatment sanitarium in Christchurch, applying there some of the experience he had acquired in John Harvey Kellogg’s booming sanitarium in Battle Creek. As his workload increased, Gustav had recruited three of Emanuel’s children, Ernest, Annie and Louise, to come and work with him. For a while that young institution was being managed by a team of Tasmanian Brandstaters. They were farm-bred, but friendly, disciplined and reliable.

Annie had plans to marry a Mr. Amyes in New Zealand. But before the wedding, she visited her family back in Bismarck, and was making plans for her marriage. But one day she went to Glenorchy for business, and rode a bicycle in Glenorchy’s main street. But in that street there was a steel tram line in which Annie’s bike wheel got caught and threw her off balance. Annie fell from her bike into the path of a heavy horse-drawn vehicle, which trampled over her, causing severe injuries from which she died shortly afterwards. This accident occurred in 1911. It was a terrible shock and a sad loss for all of Emanuel’s family, with whom Annie was a much loved daughter and sister. For Roy she was his favorite, giving him lots of personal attention, and sewing special clothes for him in ways that he admired.

With the Bismarck mill gone, Emanuel needed a new way to support his family. His career options were limited, with the little education that he had received in Bismark. He had a sizable family to support so he stuck with the life and the skills he knew well: logging and timber milling.

First Emanuel identified a large stand of tall, healthy gum trees in a mountain property in a place called Collins Cap. That was valuable raw material, available for the taking by industrious and hard-working men. It was some miles above Bismarck, reached by a winding mountain roadway. But after getting the necessary permits, Emanuel planned and constructed a new sawmill up there at “The Cap”. Then he faced one last major challenge – purchasing, hauling and installing the new mill’s heavy machinery that included boiler, steam engine, pulley system, circular saws, belt drives, and tackle for hauling heavy logs. He knew how to perform these major tasks from working with his dad, and from his own experience in Bismarck.

But there was one more item to settle before starting this major project. He had to get financing before he could purchase, transport and install this machinery. He started by demonstrating a skill and a persuasiveness in business dealings that he did not learn on the farm. Emanuel was a can-do man, and confidently approached a large fruit canning and jam-making factory in Hobart, the IXL Company, to assist with financing. Canned fruit, jam and vegetables from IXL were standard items in Australian food stores in my childhood years. We are now left to imagine the kind of serious, financial negotiations Emanuel had with the company bosses. But he was equal to the task. Emanuel had shown his engineering mettle in Bismarck, and his track record, his manner and confidence, and his reputation in the whole district, stood him in good stead. The IXL Company decided they could trust this man. They “grub-staked” Emanuel, and advanced to him the financing he needed to equip and operate the new mill. It was a big risk for Emanuel and a financial risk for IXL.

We can only imagine the drama that ensued when Emanuel procured the weighty equipment, and loaded it onto a rugged wheeled wagon built to carry heavy loads. With a team of bullocks or draught horses, he hauled it up the miles of mountain road, through Bismarck to his mill site at Collins Cap. The toughest section, Roy remembered many years later, was Pierce’s Hill, a very steep section of road between Glenorchy and Bismarck that had to be conquered before he could proceed up to Collins Cap. The effort was successful. Emanuel himself installed all that heavy equipment, and got it running smoothly. He employed a team of tough timber logging men to fell those abundant tall trees and the mill’s steam engine was soon hard at work, its winch hauling logs to the mill by steel cable over steep terrain, and driving the whirring circular bench saws. Emanuel directed the whole enterprise. He also built a respectable house for his family to live in near the mill, far from neighbors and friends in Bismarck, and a small community took shape at The Cap.

The Cap community included not only father Emanuel, but also his three youngest children, Ida, Gordon and Roy. By this time Mother Wilhemina was no longer with them. Some time before, while they were in Bismarck, she had fallen and fractured a hip, and after a period of being confined to a wheelchair, Minnie had passed away. It was a sad loss for Emanuel with whom she had partnered loyally through the rearing of seven vigorous children. She was interred in the village cemetery behind the church. Her large grave enclosure is marked today by a fine granite headstone, which also carries the name of other family members, including Annie and Fritz, known as Uncle Fred.

Sadly, the Collins Cap mill fell on hard times. Though there was need for good construction lumber, the economy was depressed in the era before World War I, and there was little money to purchase the lumber from Emanuel’s mill. Roy’s memoirs tell vivid recollections of their busy life up there on the mountain. They produced good timber, but the market failed them. Eventually Emanuel accepted reality – the mill could not survive in that economic climate. He made the hard decision, discharged his team, and closed the mill.

The family scattered. The mill is long gone, and its site is now marked by a small mountain of sawdust, plus a few items of rusty machinery. But the Collins Cap Brandstater house, the actual home for four of them as long as the mill continued to run, was still standing in 1959 when I visited the place, guided personally by Aunt Ida, who had lived there. Unfortunately the house was lost in a fierce bushfire in the sixties. After the mill had closed, Ida found domestic work for herself in the raspberry-growing area of Glen Huon and Gordon and Roy found odd jobs for themselves, mostly in low-paying farm work. When it was feasible, first Gordon, and later Roy, studied for the Adventist ministry at Avondale College. We will meet them elsewhere in another section of this website.

For Emanuel Jr, our family’s leader and pace-setter, the task for him now, at age about 50, was to find employment that would give scope to his diverse skills. It wasn’t long before he was given a responsible position as engineer, caring for the heavy machinery of a mining company near Ardlethan in western New South Wales. Tin and silver ore had to be removed from a big open cut mine, and loaded into trucks for carting to the crushing and extraction plant close by. IT was here where Emanueal spent the last two years of his life. I visited the quarry site in Ardlethan with my daughter Suzanne in 2017. We found a large open-cut quarry from which tin and silver ore had been mined and transported out to the treatment mill somewhere near. There were no remaining traces of this ore crushing and treatment plant that would have been Emanuel’s focus of attention. The ore quarry site is all that now remains of the mining enterprise to which Emanuel gave his energies and the last two years of his working life.

This is a suitable place to reflect on what kind of person Emanuel II was. He received no formal education beyond what he had received at public school in Swansea and in the Bismarck school that his father had built. Also, we have no reports of his activities in the Bismarck church. But Roy has recorded that he did serve as associate church elder with Charles Fehlberg. He must have taken active part in worship and weekly Bible study. He certainly read and studied for himself. His signature is prominent amongst the early borrowers from the small lending library in the Bismarck S.D.A. church. That original borrowers’ book is still extant, and its most recent location was in the possession of Raylene Irvine.

We should respectfully assemble a true-to-life portrait of the character of this younger Emanuel Brandstater, whose influence was spread widely over seven children and their offspring. What impression did he make on other persons of his era, besides the recollections of his son Roy? He died prematurely at only 53 years of age, in 1915, before any of his grandchildren came on the scene. So no one survives today who remembers him. But in the 1980s and 1990s some elderly Bismarck survivors were still around who I had hoped might give me some adult eyewitness glimpses of Grandfather Emanuel. So I searched out two of them, one in Hobart and the other in Sydney. I wanted to ask about the character of the man. What was his personality, his bodily presence, his speech, his behavior as a father and as standard-setting head of the family? How much of his character and example came down to us?

These old-time witnesses were two men from the Fehlberg family, Claude and Fred. Claude was the father of my good friend Carole (Fehlberg) Stanton, now living in Richmond, close to Hobart, and through her I was able to question Claude during my visit to Tasmania in 1989. The occasion was the centennial celebration of the dedication of the Collinsvale (previously Bismarck) church. Yes, Claude remembered Emanuel well. He told me that for some time during his school years he actually lived with the Emanuel Brandstater family, and observed their lifestyle at close quarters.

He related that every morning he was called, along with the rest of the family, to take part in family worship. It was not a lengthy affair, consisting of a Bible reading, sometimes a song, and a family prayer. All Emanuel’s children were raised in this atmosphere of simple, unquestioning faith in God, and they followed certain disciplines and traditions. For example, they had family worship at the beginning and at the end of every Sabbath. The closing touch was always the singing of the traditional hymn “Abide With Me.” The subsequent life stories of those family members give testimony of the strong character-building atmosphere in Emanuel’s home.

These insights into Grandfather’s household were precious to me, coming direct from Claude who had experienced them first hand. He described Emanuel’s physical presence as being “a big man”, by which I gather he meant tall and strong. Around the village, Claude added, Emanuel was everybody’s helper, a genial, kindly man. He was particularly renowned for having a natural gift for solving problems of a mechanical sort.

This particular talent was something that my father Roy emphasized to me on several occasions. His dad could fix anything. He was a carpenter and a builder. He was expert at handling the big timber that was hauled to his sawmill. He was the village “saw doctor” who could skillfully adjust, reset and sharpen the teeth on the cross-cut saws that the village men used constantly in their timber-cutting work. Likewise, he was the local clock repairer. It was rare for a family to have more than one clock, and it often fell to Emanuel’s lot to diagnose and repair any family timekeeper that was brought to him. He seemed able to turn his hand to any practical, problem-solving task. He became the owner-boss of two sawmills, and was later employed as an engineer in New South Wales.

In the memoirs that he recorded in his late years, Roy wrote these words about his father, as he remembered him:

Father was a fine Christian gentleman who, like Abraham, “commanded his children and his household after him”. He was always held in high esteem, and was an asset to any community, being competent and helpful wherever there was a need. It may be a spiritual problem, an engineering difficulty, a bit of carpentry repair, a stubborn clock or a watch refusing to go , or doing the work of an undertaker, including the making of the casket. He was the one to whom people came for help during our Bismarck sojourn. As a family we owe our moral standards, our diligence, our integrity and our efforts to achieve, to the basic Christian training which Father gave us and insisted on in our home. We never had much money, but we had a contented and happy home.

Beyond this evaluation of Emanuel’s character and personal attributes, the recollections of Fred Fehlberg were illuminating. He was the most elderly survivor of his family. I sought him out in the late 1980s or early 1990s in his Wahroonga home. When he answered my ring on his front doorbell, he looked really old and frail. But he quickly came alive when I introduced myself as a Brandstater, and Roy’s son. I explained that I wanted to hear his personal memories of the younger Emanuel. Fred described him to me as a large, strong, man, well-muscled, whose tallness and size made him appear to be the one in charge in any group of men he was with. He could be physically intimidating when confronting a bully. He would not get angry, but would speak with a voice of authority, and with a no-nonsense sternness, meaning every word that he said. Fred declared to me with a tone of conviction: “No one messed with Emanuel”.

To confirm his point, Fred related to me a story that had quickly circulated around Bismarck. For some years, Emanuel was employed as part of a work gang constructing road bridges in northern Tasmania. His family was with him during that time, and both Gordon and Roy were born in the north, Roy in Melrose and Gordon in Upper Castra. At times the work involved living in a work camp away from home and family. Some of the workmen were pretty rough, and liked to play jokes and pour ridicule on a straight, non-swearing, non-drinking man like Emanuel. On one occasion a member of the workforce short-sheeted Emanuel’s bedroll and put inside it a filthy dead creature. Emanuel soon learned who was the culprit, and warned him not to try that nonsense again, or else! Well, the perpetrator did not take the warning seriously, and played a similar trick again, to raise a laugh from his workmates. But Emanuel was as good as his word. With hands and fists he gave that man a physical thrashing that beat him up badly. Bruised and battered, he was unable to work for several days. The rest of the gang were awed, and after that Emanuel was left in peace. For Emanuel, gentleness must sometimes be strong.

Now we return to the tin mine at Ardlethan and the final closing of Emanuel’s story. While working at the mine in early 1915, Emanuel contracted typhoid fever, due probably to poor sanitary conditions and polluted water at the mine. Seriously ill, he was transported from Ardlethan to the hospital at Narrandera, about 60 miles away. Word of his illness was sent to his son, Roy, now almost seventeen years of age, at Avondale College. Roy promptly took leave from his work at a local timber mill, and took a train to Narrandera. There he spent several days at his father’s bedside, talking with his dad, who seemed to be getting better and gaining strength. But one morning at his hotel, Roy was given the stunning news that his father had died overnight. Very likely the cause was heart failure, a known complication of typhoid toxemia. A funeral was arranged by the mine owner, and Roy was the only family member present, to watch sadly as his beloved father was laid to rest in the Narrandera cemetery. This sad event took place in early 1915. He was just 53 years of age.

During the nineteen seventies or eighties, I asked several family members about Emanuel’s burial place. Nobody seemed to know where he was buried. Apparently no one from the family had visited the gravesite since his burial, sixty years before. So I drove out to Narrandera, some 300 miles west of Sydney, to hopefully locate the grave, and to pay respect to a man so significant to me and to the whole expanding family. He was truly a man’s man, an admirable grandfather. At the Narrandera cemetery the custodian showed me a gravesite map, and Emanuel’s grave was clearly indicated. But when I made my way to that site, it was plain, bare earth. There was no marker of any kind to identify the grave, though around it were many other graves with engraved headstones. I remained at the grave for a long time, in quiet reflection and grateful prayer, thankful for all this man had been. I resolved that soon a marker would be installed to identify that sacred place.

After leaving the gravesite that day, I stopped at the town’s hospital, and I introduced myself to the matron. I asked her if it was possible for a physician like me to inspect the medical records of a man, my own grandfather, who died in the hospital in early 1915. Perhaps the hospital records could add some details to the little we knew about Emanuel’s last illness and death. The matron answered with great sadness. Yes, she would love to show me those records, the old ones from early 1915. They had been held in storage for many decades, but had been destroyed just three weeks before my arrival. After sixty years I was too late, by just three weeks.

My next stop was the newspaper office where all old files of the local newspaper were kept, going back to its beginnings. I searched carefully through several old issues for any mention of a fatality occurring in the hospital near to the date I had for Emanuel’s passing. But I found none. I did find, however, several days beyond the date of his death, a report from the hospital administrator and the matron at that time. In the report there was reference to several recent deaths caused by an outbreak of typhoid in the tin mine at Ardlethan. This was the closest we will ever see to a published report of Emanuel’s final exit. It was a lonely passing for a man of exceptional caliber and character who deserved much more.

A black marble headstone now marks the grave of Emanuel Brandstater Jr

Rest In Peace …….. Grandfather Emanuel